|

| The English Bookstore on Kralja Petra, Belgrade |

The national language of Serbia is Serbian, which is a Slavic language based on a Latin grammatical structure. That means the daily conversation covers three genders, eight tenses and seven declinations, which any foreigner will find virtually impossible to master. Wisdoms conveyed in Serbian supersede Boolean logic, as demonstrated by the double negation feature, which never ceases to flummox me. The perfectly proper sentence “Nista nemam” literally means “Nothing I not have,” which logically means “I have everything,” but which every Serb understands to denote a complete absence of possession.

|

| Seen at Tesla Airport Belgrade, Serbia |

I’ve heard Serbian people say things like “all the night long,” or “wash car with the soap,” and then proceed to use words like “undulation,” “torpid” and “ostentatious.” I don’t know enough about the Serbian language to make a valid assessment but I’m guessing that the general Serb commands an incredible vocabulary and library of metaphoric images.

I was at an Internet café, nervously pacing between computer and printer, when the girl behind the counter said, “Don’t worry; I’ll fetch them for you.” Another time I met a fellow on a street corner holding a hand on his head, looking troubled, and I asked him what was up. He pointed at a piece of billboard that had come flying from a stand and said, “That struck me.”

A native from the Unites States would have said, “I‘ll get‘em for you,” and “I got hit.” A Brit would have invoked body parts at both occasions. An Aussie would probably have said something not relevant to either situation, and incomprehensible to anyone not an Aussie.

In the short period I’ve been here, I’ve only read a few books that were translated into English from Serbian. What I’ve noticed is that the Serbians like their texts as Baroque as Mozart, their style verbose and meandering as if every article is a play. It almost seems that the subordinate clause is the primary means of verbal expression in Serbia.

“People who grew up on a stone hill beneath such an exciting panorama cannot but be broad of gesture, stormy of temperament and changing of mood. These people, who stay in their city despite everything, even as history destroys and crumbles it, covering the land with layers of leaves and remnants of previous settlements and past civilizations, such people are capable of building their city anew, in a relaxed and unpretentious way; they are capable of building a city of human proportions.”

- Momo Kapor; A Guide to the Serbian Mentality.

|

| Book sellers in Belgrade, Serbia |

The Serbs are not only polyglots, capable of astounding precision in various languages, or so hooked on books that there are more bookseller than hot dog vendors on the streets of Belgrade, they also maintain two alphabets: the Latin one that I now use to talk to you albeit expanded with all kinds of dots and jingles to form 30 separate letters, and Cyrillic. Cyrillic was the original alphabet of the Serbian culture (standardized in 1814), and it’s still ubiquitous in Belgrade. It’s almost as if the heartwarming hospitality of the Serbs comes with a friendly warning that the heart of Serbia is quite private and guarded with a public key. I like that.

|

| Plato Book Store (Menu of the coffee corner) |

In order to play a part on the global marketplace, the Latin alphabet was adopted by Serbia in 1830 (the same happened in many other countries, such as China and Japan). But because the original Cyrillic is far richer in sounds than, say, written English, the Latin alphabet had to be augmented with diacritics. This richness is consonants is so strong even that the Serbian language has words that are written without vowels. Utterly curious to a foreign observer are words like krnj (meaning defective) or krst (means cross).

|

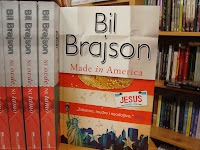

| Bil Brajson (Bill Bryson) Made in America |

The title of his book Made In America remained unchanged, and no Serb in the bookstore seemed to mind.

Follow my blog with bloglovin

No comments:

Post a Comment